I’ve just finished reading an action-packed children’s story about time travel, history, mystery and friendship (Vesuvius by J. D. Fennell) and, after I’d added it to my shelf of ‘enjoyed’ children’s books, I permitted myself a few moments to consider what this book has done for me.

That might sound slightly odd and demanding but I think we should ask things from the books we read. For me, the answer depends on whether I’m reading a book as a writer or as a consumer.

As a writer, I scrutinise stories, looking for inspiration, examples of great writing, words I can use, expressions that impress and amaze me and many other elements. However, as a reader, a good book offers up so much more. During school writing workshops, I always ask children what they are reading and why they like it. What I discover every time, without fail, is that they get exactly the same things as I do from reading fiction.

Expression: In stories children see characters expressing themselves. Good dialogue helps to get across a character’s likes, dislikes, desires, fears and doubts and sometimes this resonates with them. Children are offered different perspectives on how to handle people, situations and issues by reading what characters do in fictional stories. Reading about characters trying to overcome hurdles and problems is perhaps the literary form of coaching or counselling.

Identity: Do you ever have a moment where you identify with a character in a work of fiction, whether it’s over something positive or negative, emotional or physical and have a, ‘That’s me!’ moment? Identifying with someone else, even someone fictional, gives children a sense of solidarity, belonging and common ground. It’s wonderful and reassuring to feel that you’re not alone.

Dialogue: When dialogue is good in fiction, we feel like we’re standing inches away from our book characters, watching real life. Children learn so many things from dialogue, including regional and international language, dialects, slang and how conversations influence and affect people, both positively and negatively. Awareness of the different ways of verbally approaching people and issues is of benefit to everyone and fiction has a brilliant habit of helping us do this.

Problem Solving: One of the cornerstones of writing children’s fiction, is to present our characters with problems and obstacles. No one wants to read about a quest to find a golden key that is easy and quickly solved. But showing how characters handle their worst fears being realised, gives children insight into how problems might be solved and how hurdles can be overcome. We all love a character who defies the odds, beats the bullies or succeeds in a challenge and we enjoy the process of how they manage it even more.

Relationships: Reading fiction gives children exposure to a wide variety of relationships and how they work; from friendships, romances and parent-child relationships to educators, peers and animals. Children can learn about the rich diversity of both positive and negative relationships and their impact on characters in books. This often translates into reinforcing or highlighting their own relationships and challenges them to consider how these relationships make them feel.

One example of this is Jess and Jude Carter in Lauren St John’s Wave Riders. At first glance, their lives consist of exciting adventure and an opportunity to be part of a glamourous, wealthy family. However, they soon discover that being on their own might be preferable to being part of a toxic, unloving family environment. Lauren St John challenges the reader to see beneath the veneer at what the relationship is really about.

Diversity: I am currently reading a fabulous story about magic, mystery and friendship, that is also about a working-class black girl in a predominantly white, middle-class school. Along with the quest, we she how she deals with others’ fear of her and how this fear very quickly morphs into hate (Amari and the Night Brothers by B.B. Alston).

As I turn the pages, the word diversity comes to mind, where we appreciate and value what makes people different, as opposed to merely tolerating it. Stories allow children to explore these differences in a safe, nurturing, quiet environment. They allow self-reflection, contemplation and the time to explore their thoughts and feelings about themselves and others.

Personal Responsibility and Influence: Whether it’s Jess and Jude Carter in Lauren St John’s, Wave Riders, Eliza in Jess Butterworth’s, Swimming Against the Storm or Maia in Eva Ibbotson’s, Journey to the River Sea, these characters all display their belief in personal responsibility. They use their power and energy to influence change for the benefit of everyone. As an adult, I find these stories liberating, motivational and encouraging and the children I’ve spoken with feel exactly the same.

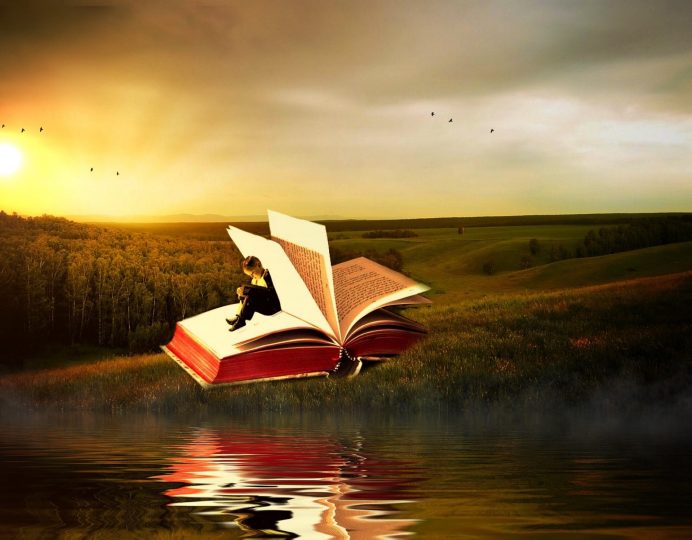

Escapism: In a world of school, parents, friends and reality, children need some form of escapism. Good books give children the opportunity to get lost in a fictional fantasy world, become absorbed by a mystery or entertained by a humorous story. Who doesn’t enjoy being transported to a new, exciting world, different to our own?

Humour: We all have different, weird and wonderful senses of humour but the moment a book makes us laugh out loud, they’ve got us. Many children I speak to cite humour as the main reason for reading. They want to feel that sense of joy, laugh at the outrageous things they would never be able to do themselves and be silly for just a while in a world that can often be so serious or pressured.

Experience: How we interpret what a story means, what the characters stand for and the feel of the language, depends on our own life experiences. For children, life experiences can, amongst other things, include culture, identity, self-image or primary influences. Even at a young age, children make judgements about characters and behaviours, based on past experiences and role models. A sense of right and wrong and fairness will influence how they feel about a character, a situation or a decision.

Have you ever raced through a good story, yet not be able to quite put your finger on why it was so good? Some children tell me that they like the ‘feel’ of a story and can’t explain any further. Perhaps it’s the language, the flow, the mood, the structure, the description, dialogue or meaning that produces such positive feelings. Maybe the author has tapped into the child’s greatest fear or joy or created a world of escapism. Perhaps being made to think, puzzle and explore is what feels good to some children. Good fiction does all of this. It’s more than just a story.

Click here to see some of my favourite children’s books.